SKIRTING THE BORDER

Only the narrow Yalu and Tumen rivers separate neighbors China and North Korea. The river banks are so close to each other that people can easily see across the border, and into each other’s lives.

Dandong, in China’s Liaoning Province, is acutely aware of its unique position as a neighbor to North Korea. It has capitalized on this by building a thriving tourism business for sightseers curious to gain a glimpse of life into the hermit lands across the river.

Thousands of Chinese and South Korean's journey to Dandong and use binoculars to peer across the divide. Sinuiju, the capital of North Korea’s North Pyongan Province, is only a few hundred meters away, but the two cities could hardly be more different.

Blocks of tall apartments dominate the skyline on the Chinese side of the river together with other signs of modernity. On the far side of the river, Sinuiju lies drab with collections of nondescript concrete buildings and what appear to be many dilapidated factories. Tall industrial chimney stacks occasionally plume out puffs of black smoke, and a small abandoned amusement park offers a sad, derelict, rusty Ferris wheel. For visitors to Dandong, the view across to Sinuiju does not look very inviting. It is a vista that has barely changed in 40 years.

As night falls, the difference between Dandong and Sinuiju becomes most stark. The Chinese city is ablaze with neon lights and dazzling skyscrapers. By comparison, a few lonely windows flicker from Sinuiju.

For the Chinese peering across the river, the fascination with North Korea extends to more than just its isolation; there are historical parallels. It reminds them of China in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, when they were also closed off from the outside world. Common remarks overheard as Chinese squint through their binoculars, is that North Korea is not as advanced as China, their economy is very backward, but it seems like they're doing their best to build it up.

Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge

The Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge connects the cities of Dandong in China and Sinuiju of North Korea. The combination rail and single-lane road bridge is one of the few ways to enter or leave North Korea.

Dandong is the port of call for dozens of trucks crossing out of and then back into North Korea each day. It is Pyongyang’s most crucial conduit for commerce with the outside world.

The bridge reportedly carries approximately 80% of the trade between the two countries. It is also the busiest route for human travel between the neighbors, with virtually all ethnic Korean Chinese required to use it when traveling to visit their North Korean relatives.

The Imperial Japanese Army constructed the bridge in 1943 during their occupation of the Korea Peninsula and their puppet-state of Manchukuo (present-day northeast China). Formerly known as the "Yalu River Bridge,” in 1990 it was renamed by the Chinese and North Koreans as the “Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge” to illustrate the close relationship between the two neighbors.

Common thinking is that pedestrians are not permitted to use the bridge to cross between either side. However, there does appear to be exceptions granted to this rule as occasionally Chinese families are seen walking the single lane roadway between the two countries.

Just meters to the south of the Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge are the remains of the original Yalu River Bridge. The Americans destroyed the bridge in 1951 during the Korean War. The ruins of the bombed bridge, which now only go halfway across the river, are known as the Yalu River Broken Bridge.

Repeated bombings of Yalu River bridges by the United States were an attempt to cut off Chinese Communist troops. The Americans hoped to prevent Chinese supplies and soldiers from reaching the North Korean frontline to assist North Korean fighters. The bombings also were a planned element of the overall greater strategic bombing campaign to crush North Korean aggression. More than one hundred B-29 and B-17 heavy bombers, as well as F-80 fighters, pounded the bridges in late 1950 and again in early 1951.

Aircrews were explicitly briefed to avoid dropping bombs on the Manchurian (Chinese) side of the river, with the Yalu bridges being severed by destroying spans in the North Korean half of the river.

The destruction of targeted sections of the Yalu River bridge was only intended as a temporary halt to the Communists. American war strategists realized that in early December the river would freeze over with ice that was thick enough to take military traffic.

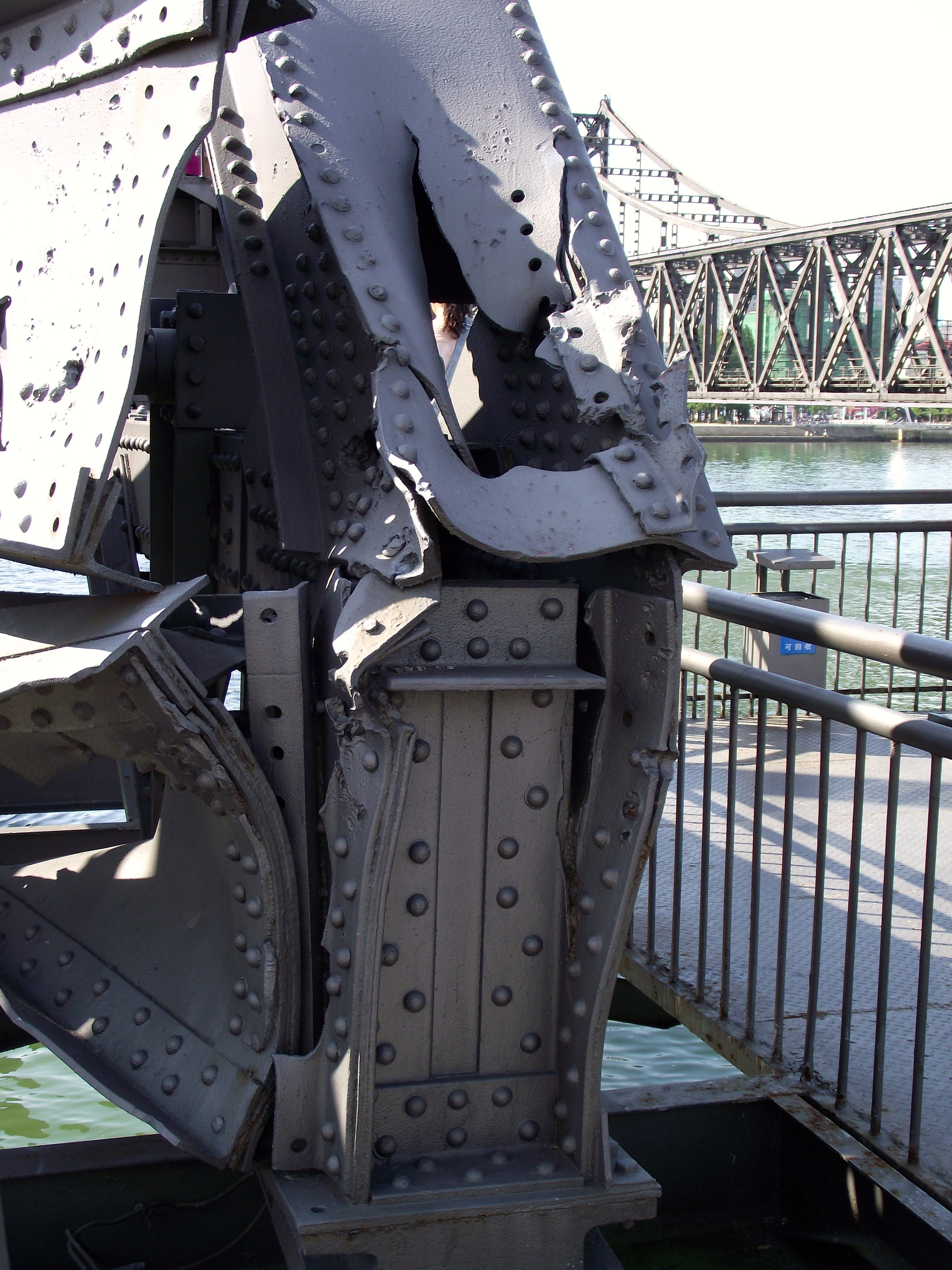

The remains of the Broken Bridge has been refurbished by the Chinese and it is now a significant government-sanctioned heritage site. The bridge's steel beams still wear scuffs and holes from bullets and shrapnel. Some beams are left bent or mangled. The bridge's rotating span mechanism that originally allowed ships to pass through the bridge, remains twisted and smashed as it was on the day the American bombs hit.

The Broken Bridge now abruptly ends at the mid-river point, where a recovered, unexploded but now deactivated, US Air Force bomb used to pound the bridge is displayed.

Over the years, the Broken Bridge has carried multiple meanings for the Chinese. Originally it was a symbol of humiliation, a record of construction by Japan, a ruthless occupying foreign power.

Four decades later, it became a shocking illustration of how another invading force, the United States, crossed the Pacific, reached the edge of China and armed with heavy firepower destroyed the North Korean border crossing.

Now, in present times, it is a tourist attraction and viewing platform for visitors to gaze into the hermit kingdom. When walking onto the Broken Bridge, you pass an impressive, larger-than-life bronze sculpture of soldiers from the Chinese People’s Army. Two words in both Chinese and English are anchored before the commanding officer’s feet: “For Peace.”

For many visitors to Dandong, the walk along the Broken Bridge to the river’s midway point doesn’t fully satisfy their curiosity to peer into North Korea. Chinese ferry operators at two piers on the waterfront enable tourists to ride ferry boats beyond the river’s midway ‘border’ to within meters of the North Korean shore.

A few minutes' walk north of the Friendship Bridge is a pier where boats depart for a short cruise that pass by the North Korean school on Wihwa Island. Children in their uniforms complete with red kerchiefs worn around their neck occasionally wave.

Passing through gates in the barbed-wire fence, North Koreans from the dilapidated residential area walk to the riverbank. They check their fishing nets and wash clothes in the river while border guards in watchtowers and camouflaged concrete bunkers monitor the river activity.

At the pier just south of the Broken Bridge ferries cruise across the Yalu to within meters of the base for North Korean patrol boats and a series of North Korean industrial docks and warehouses.

An hour north of Dandong, Chinese speedboat and small ferryboat operators cruise across the river and into North Korean territory allowing an up-close view of border guards and villages.

Navigating around the North Korean river islands allows close encounters with Korean farmers, fishermen and the occasional ill-equipped soldier.

The speedboats cruse close enough to the North Korean shore that in winter the plumes of breath exhaled by soldiers chanting and marching in formation is seen. At times these soldiers point their weapons at the boats in mock aggression, most likely a half-hearted warning rather than a genuine attempt to intimidate.

Some boatmen sell small bags of bread and biscuits to their passengers, which are then thrown onto the shore for border guards and children to eat. In some areas of the river North Korean rowboats come aside the Chinese speedboats to sell packs of North Korean cigarettes, dried fish, ginseng, salted duck eggs and kimchi to the sightseers.

In 2018 Beijing clamped down on these river exchanges as part of a campaign to reduce border smuggling. Chinese boatman dotted along the border used to trade freely with their counterparts on the North Korean side. Now, following wave after wave of sanctions, these interactions and any trading between the river tourists and North Koreans have been driven underground.

YI Bu Kua (One Step Across)

Thirty minutes drive north of Dandong, close to the easternmost section of China's Great Wall, the Yalu River border dwindles to a narrow stream.

This point is known as "Yi Bu Kua"(One Step Across).

Apart from a sign reminding visitors of etiquette when at the national border of the Peoples Republic of China and the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea, there is no visible indication that the other riverbank, mere meters away is North Korea. There are no customs officers or stationed border guards. Not even a fence, just the narrow stream.

In the warmer months when looking across to North Korea, there is nothing to see other than tall grass and beyond to fields of crops. In winter when the vegetation is not as lush, a North Korean guard post becomes visible together with a security fence that was obscured by the long grass that grows in the summer.

In the past, Yi Bu Kua has been a departure point for border tourist cruising; however this business has been abandoned, and the area is no longer a highlight on the itinerary for Chinese border tourists.

Reaching this narrow point of the river is now a 20-minute rough and rocky terrain hike, north along the riverbank from the Great Wall. In the summer heat, if it were not for the Chinese border etiquette sign, hikers could be tempted to cool off with a swim in the stream once reaching Yi Bu Kua.

The sign politely reminds visitors not to climb or cross any separation obstacles, throw any objects into North Korea, or converse or exchange objects with people on the other side of the border.

There are reports from travelers that North Korean border guards have emerged suddenly from the grass on the far bank and asked for packs of cigarettes to be thrown across to them. Backpacker legends tell stories of daredevils that have swum across the stream, including one of an Italian journalist that crossed here, was well fed by border guards, questioned and sent back to China a few days later.

Refugee Containment

The 2017 war of words between USA President Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un sparked fears that the escalating rhetoric could spill over into a military confrontation.

Threats, talks, sanctions, and missile tests are not new developments in the American and North Korea relationship; however tensions had reached such an elevated level that China worried that instability in North Korea was increasingly likely with a potentially messy collapse of the Kim Jong-un regime.

For decades, Chinese policy on North Korea has centered on maintaining stability in North Korea fearing a collapse that would result in refugees flooding across the narrow Tumen and Yalu rivers into the economically vulnerable northeast of China.

Sources in Dandong reported in late 2017 that the Chinese government had cleared a large area on the edge of town just to the south of the Great Wall. The area could be used as a camp to house up to 100,000 refugees following an attack on North Korea.

In late 2018, Behind the Curtain visited the location and found the large cleared area secured with razor wire fences. It is ready to contain a refugee population and keep them separated from the outskirts of Dandong.

Hushan Great Wall

Tucked away unobtrusively to the northeast of Dandong lies a steep, green-sided pair of peaks known as Hushan Mountain. The name of the mountain means “Tiger Mountain," named because the two towering peaks resemble two tiger ears pricking up into the heavens.

It was here that in 1989 that a newly uncovered section of the Great Wall of China was excavated and restored. The Hushan Great Wall was built to strengthen the frontier defense in 1469 during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and is the easternmost point of the huge military defensive system. The wall was built to prevent intrusion from Mongol forces and Jurchen tribes to the north and to protect the north-eastern border from Japanese or Korean attacks from the south.

Unlike other sections of the Great Wall of China, this section sees comparatively few tourists. Sightseers generally travel to the Hushan Great Wall simply for the scenery.

From the top of the wall, you can see vast distances; across a stream to fields of crops growing in the fertile lowlands. Beyond the fields, lies an air force base. What some visitors may not realize, is that they are not peering down into China; the areas beyond the stream are in North Korea.

The Chinese identification of Hushan as the eastern end of the Great Wall in 2009 was met with skepticism by Korean academia. Many Korean historians identify the site as the Bakjak Fortress of the Goguryeo Kingdom.

Kwon Hee-young, a professor of history at South Korea’s Academy of Korean Studies has gone as far as to allege that ulterior motives have driven the Chinese to remodeled the fortress walls in the style of the Ming Dynasty erasing the traces of the true Goguryeo heritage.

Kwon Hee-young believes that China’s motivation to hide the Korean heritage of the site is driven by a narrow-minded political objective by Beijing to erase all of the cultural traces of ethnic minorities in China’s northern regions and absorb these cultures as part of the Han Chinese people's heritage.

Kwon asserts that the UNESCO's World Heritage projects, such as the restoration of the Hushan wall, is designed to safeguard the legacies of each nation's contributions to history as the heritage of humanity, but has been misused as a tool for China to remove differences between ethnic groups and create a new Chinese ethnicity.